Flash Gordon and the Dead Hand of Historical Editing

Despite a predictable controversy over its "problematic" portrayal of Ming The Merciless, Flash Gordon remains very much alive

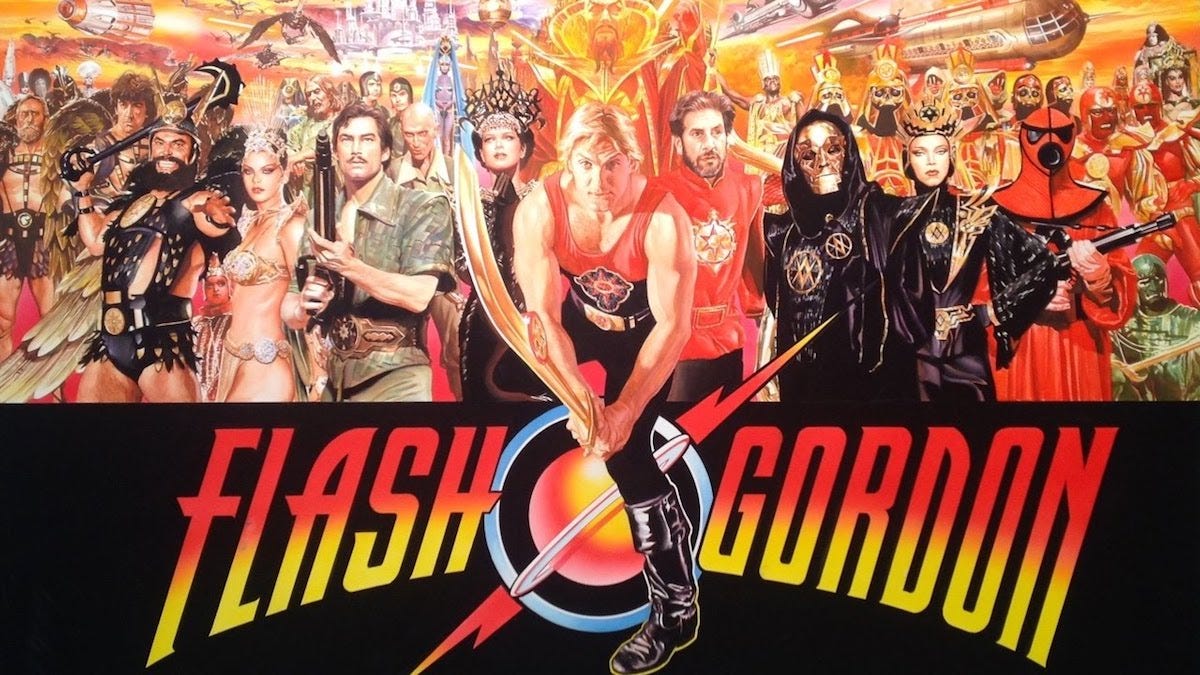

Flash Gordon is camp. Very camp. And then camper still.

It is unbelievably, eye-wateringly ostentatious on a scale that would make Graham Norton shudder. It features respected actors (mostly American, some British) and comes drizzled with oodles of late 70s Hollywood money, invested to create a cinematic extravaganza for audiences still hungry for sci-fi blockbusters after the success of Star Wars.

Over the past few years, however, amidst the social media over-agitated culture wars, 1980’s Flash Gordon has found itself in the spotlight (or crosshairs, depending on your point of view) for being “problematic” and in need of historical editing along strict identity politics lines. In particular, it has generated a certain amount of frothy controversy, due to Max Von Syndon’s pantomimesque portrayal of Ming the Merciless in the movie.

According to Ben Child in a June 2019 Guardian article, “It is not hard to pinpoint the mindset that inspired the creation of Flash Gordon’s extraterrestrial nemesis, Ming the Merciless, back in 1934. When the scariest thing you can imagine invading the Earth is an ornately dressed gentleman of apparent East Asian extraction, it’s clear you’re not really frightened of aliens at all.”

Child goes on to argue that, “Of course, Max von Sydow’s towering performance in the campy 1980 film doesn’t help here, even if those costumes and makeup on a Swedish actor now seems pretty repugnant.”

As reported by the BBC in December 2020, the British Board of Film Classification had also decided to add a warning to the movie’s home media re-release, due to its “discriminatory stereotypes”.

That year the BBFC gave Flash Gordon a 12A rating on its reissue (as opposed to a more lenient A rating at the time of original cinema release, equivalent to a PG today). In the eyes of BBFC senior policy officer Matt Tindall, this change was also down to Flash Gordon’s portrayal of Ming the Merciless, as well as the violence and adult language in the movie.

“Ming the Merciless is coded as an East Asian character due to his hair and make-up, but he’s played by a Swedish actor in the film,” Tindall told the BBC at the time, “which I don’t think is something that would happen if this were a modern production, and is something that we’re also aware that viewers may find dubious if not outright offensive.”

In taking this position Tindall was pointedly referencing the growing controversy over the portrayal of culturally identifiable characters on screen and the discussion as to whether such portrayals allow for interpretation or parody. Russell T. Davies, on the back of his success with Channel 4’s It’s a Sin a year later, has also weighed in on this debate, by asking if it is credible for heterosexual actors to play homosexual characters in dramas such as his.

All of which may make sense today, to a particular cultural-political constituency, though it would not have done so back in 1980 when Flash Gordon was originally released.

That year, hopes were high on the part of the movie’s producer Dino De Laurentis for his expensive, colourful reinterpretation of the 1930s original cinematic series. Rock band Queen had been contracted to record the Flash Gordon soundtrack (which fared better in terms of sales than the movie), whilst American football star Sam J. Jones was persuaded to strip on camera for the movie.

In the eyes of De Laurentis (also responsible for Serpico, Death Wish, The Shootist, Conan the Barbarian and Blue Velvet) how could such a heady, colourful concoction fail?

As Flash Gordon begins, director Mike Hodges takes Flash, Dale Arden and Doctor Hans Zarkov to the Planet Mongo after the Earth is devastated by a weather catastrophe, and then lets his characters run amuck with the desires, emotions and plans of Ming the Merciless somewhere high above the skies. By the end of a not entirely coherent 111 cinematic minutes, the Earth is saved and our heroes applaud.

There is even the tantalising possibility of a sequel dangled at the end of Flash Gordon, as Ming’s laughter bleeds into the squealing guitar of Brian May and the credits roll.

Featuring a pre-Bond Timothy Dalton, virtually twirling his moustache in a satire of 30’s machismo, Flash Gordon is probably best remembered for Brian Blessed’s full-on beast mode performance in the movie, and his line (deliriously delivered) that “Gordon’s alive!”

Flash Gordon was always, modern cultural nervousness aside, an exaggerated crowd-pleaser of a motion picture, and a knowing pastiche of the ideals and adventurism of the 1930s original. Though it may not quite catch fire as it was intended, the movie has beautiful women (wearing little) and handsome men (also wearing little); whips get cracked, thigh-length leather boots creak, and its dreamy, druggy visuals are infused with a kind of TV splendour that, in its kitschy way, equates to something resembling visual charm.

Over the years the critics have not exactly rushed to praise Flash Gordon during its various re-releases.

“An irrelevant campy sci-fier,” wrote Dennis Schwartz for Ozus’ World Movie Reviews, whilst according to Christopher Null of filmcritic.org, Flash Gordon is “as good and as bad as moviemaking gets”. Roger Ebert continued in the same vein for The Chicago Sun-Times, though he did also give a nod to the movie’s entertainment value: “Is all of this ridiculous? Of course. Is it fun? Yeah, sort of, it is.”

However, it was Pauline Kael who managed to sum up the appeal of the (slightly guilty) pleasures to be found in Flash Gordon. “Like a fairytale set in a discothèque in the clouds,” she wrote in 1980 on its original release, “Flash Gordon is simply out to give you a good time.”

Which pretty much sums it up.

It is interesting to note that, at between $20 and $27 million, Flash Gordon was an expensive movie to make back in 1979. It went on to generate a disappointing $27 million at the box office and from home media sales, though it did pick up a growing cult following with each reissue.

Compare that with Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, also released in 1980, at a cost to United Artists of around $50 million, but which destroyed the studio in the process.

So, is Flash Gordon now (and forever) to be condemned as “problematic” and in need of historical editing, or possibly even cancellation? Or is it better and fairer to simply enjoy the movie for what it is; a whimsical celluloid fantasy, as devoid of genuine political meaning as it is filled with camp theatrics?

Only time (and the historical editors) will tell.